The Dancing Plague Of 1518 Was The Moment People, Literally, Danced Till Death

I have to admit: I hate dancing more than almost anything else in the world. I shy away from weddings like a vampire from a crucifix. The thought of dancing can make me break out in a cold sweat (at weddings, it’s actually great, because it seems like I’m only sitting down because I’ve been dancing a lot and sweating), and any song that turns out to be a dance becomes less appealing to me. So, I admit that the moment I first read about the Strasbourg dancing epidemic in the 16th century – Known as the dancing plague of 1518 – I almost saw my worst nightmare come true. I remember shouting something like “Ahhhh!” and “Bahhhh!”, doing the movements of a drunken zombie with a tantrum, and leaving the room with a speed that would not have embarrassed someone dodging a serial killer in a slasher film.

For someone like me, who thinks of dancing as a sophisticated form of torture invented in ancient times to punish people, this event takes on an extra dimension of horror. Picture this nightmare: You wake up one morning, and suddenly your legs start moving rhythmically and won’t stop. No matter how much you beg, no matter how much you scream, your body keeps dancing non-stop, hour after hour, day after day, until you collapse from exhaustion or even die. According to the stories, some would say myth, this is precisely what happened to hundreds of residents of Strasbourg in the 16th century. This is not a wedding where you can try to escape from the dance floor (“Oh, look! They’re going to bring a new dessert!”) or a party where you can avoid it with more interesting programs (full disclosure: I haven’t been to a party in 20 years), but a complete physical compulsion and lack of control over your body. Body Horror is scarier than any movie you’ve ever seen.

So what exactly happened in the summer of 1518? Why did people start dancing, and what were the results of this crazy dance? In the following review, part of our series of articles on scary dances, we will present the main questions about this unusual event, some of which remain unanswered to this day.

What Was The Dancing Plague Of Strasbourg?

The dancing plague occurred in July 1518 in the city of Strasbourg, a free city within the Holy Roman Empire at the time, in the French province of Alsace. At the peak of the event, hundreds of citizens began to dance unwillingly or even uncontrollably for days on end. Still, the phenomenon had already started earlier, likely due to the influence of one woman.

Do you know that moment when someone brave, unaware, or annoying suddenly gets up and starts dancing, trying to sweep everyone after them? So in Strasbourg, this “life of the party” was probably a woman named Frau Troffea. One bright day, she began to dance enthusiastically in the city streets alongside her daughter, and continued for six days. Legend has it that the locals viewed this strange dance as welcome entertainment in a city that lacked many entertainment options (remember, in the 16th century, there were no horror films). But what started as an innocent street performance by someone who was perhaps a little eccentric quickly turned into a much larger and more sinister phenomenon.

According to reports, within a few days, several dozen more people, mostly women, joined in. The phenomenon spread like a virus. A month after the debut dance, the Strasbourg dance troupe numbered about 400 people. The dancers entered a trance-like state, their bodies continued to move in rhythmic movements, without conscious control, and without stopping. They danced for days until they were exhausted and unconscious, and in some cases until they died. Their bodies continued to move in rhythmic movements, without conscious control and without stopping.

How Long Did The Dancing Plague Last?

The local authorities were entirely baffled by the unusual phenomenon, especially when the local doctor ruled out many other causes, even supernatural ones. At one point, the phenomenon was considered a “natural disease,” whose cause was, surprisingly, the “hot blood” of the dancers. In those years, a standard medical treatment called “bloodletting,” or phlebotomy, was based on a relatively simple principle: The assumption was that the blood of patients was “contaminated.” Therefore, they believed we can treat various problems and diseases by deliberately losing blood, sometimes in commercial quantities, so that the concentration of “good” blood would increase and the “bad” blood would decrease.

Quite surprisingly, the authorities opted for an alternative, even stranger solution. They tried to encourage the dancers even more, thinking that endless dancing would allow them to “get it out” of their bodies. They opened large dance halls and built them throughout the city, hiring professional dancers and even employing a band that played music in real time. The hope that the dancers would be cured if they danced non-stop, day and night, proved inaccurate. The death toll rose due to exhaustion, heart attacks, strokes, and other causes. Other attempts we know from the worlds of horror, such as mass exorcisms, also failed.

How Many People Died From The Dancing Plague?

The physical consequences of the epidemic were deadly. Hundreds of people had to dance for weeks, or even months, until they collapsed or died of exhaustion. The dancers suffered from extreme fatigue, dehydration, and complete physical collapse. The phenomenon did not distinguish between men and women (although most of the dancers were women), nor between young and old, or rich and poor.

One of the most complex questions about the Strasbourg dancing epidemic is how many people actually died as a result of it, an issue about which there is neither consensus among scholars nor sufficient historical evidence. Some sources claim that the epidemic killed about 15 people a day for a specific period, which means that in total, several hundred people died. Several scholars have written academic papers on the subject, although most are based on later accounts of the event rather than real-time accounts.

Official sources from the city of Strasbourg do not specify the number of deaths, or even whether there were any victims at all. There is also some disagreement about the identity of the first dancer who initiated the event and the number of participants, which ranged from approximately 50 to 400.

The Dance Mania Takes Over Europe

At this moment, it’s essential to note that the Strasbourg incident and the dancing epidemic we are dealing with are not isolated cases. This is where the concept of “Dancing Mania,” also known by its official name, “Choreomania,” comes into play. This phenomenon occurred primarily in Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries, referring to groups of people dancing simultaneously and in an incomprehensible manner, sometimes involving thousands of people at a time. The mania affected adults and children who danced until, seemingly, they collapsed from exhaustion and injuries, and sometimes died.

One of the first major outbreaks was in Achen, in the Holy Roman Empire (within present-day Germany), in 1374, and it spread rapidly throughout Europe; a particularly notable outbreak occurred in Strasbourg in 1518 in Alsace, also in the Holy Roman Empire (now in present-day France), and then to cities such as Metz, Utrecht, Cologne and others.

The Strasbourg plague was not the earliest and probably not the most widespread, but it was the most widely documented in historical documents, sermons, local chronicles, and other sources.

What Caused The Dancing Plague Of 1518?

Over the years, researchers have proposed several possible explanations for this enigmatic phenomenon, yet a definitive answer remains elusive. The common denominator is the claim that the dancers did not do it of their own free will, and certainly not to enjoy themselves (really, because how can you enjoy dancing?). There were reports that some dancers writhed in pain and begged for help during the dance.

Food Poisoning

One of the most popular theories links the plague to an infection with ergot, a species of toxic parasitic fungus, the physical manifestation of which resembles mold that develops on grains (especially rye). A person who consumes this type of fungus may experience Ergotism Poisoning, the possible manifestations of which include a burning sensation in the body, convulsions, nausea, cramps, and, in extreme cases, necrosis or death. These infections were common in ancient times, as evidenced by the fact that, for example, in 944, approximately 40,000 people died in France due to consuming fungi or grains contaminated with ergot.

In ancient times, ergot had a variety of uses, primarily in combination with medicinal plants, such as relieving the pain associated with labor. On the negative side, it was used for military purposes, including chemical warfare or even trying to influence a person’s mind (including, among other things, to make them provide information that they were not supposed to convey). To this day, many use ergot to produce the drug LSD.

Did a fungus, which somehow ended up in the bread of the residents of Strasbourg, cause the dancing plague? It’s possible, but the answer is probably no. The large number of dancers and the prolonged duration of the epidemic likely point to another factor.

Mass Hysteria, Exorcism, And What’s In Between

The theory currently accepted by most researchers is that the dancing plague was caused by mass hysteria – a psychological phenomenon in which a group of people develop similar physical symptoms, without a clear medical cause.

In the case of Strasbourg, the social, economic, and religious pressures of the time created fertile ground for such a phenomenon to break out. The period was challenging for the residents of Strasbourg, with hunger, disease, economic, and religious pressures. Under such conditions, a phenomenon like the “dancing curse” could spread quickly, especially when the community believed in supernatural powers.

Some experts believe that a large part of the residents of Strasbourg believed in spirit possession, or, as we know it from horror movies, exorcism. It is a psychological condition in which a person believes that external forces have entered their body and decided to control them, removing their normal identity from the picture. Whether it is ancestors, spirits, theological entities (such as angels or gods), or something else, these demons may be responsible for the phenomenon to some extent by contributing to the mass hysteria.

From Blood to Spiders: Medical Theories of the Era

The fact that similar cases have occurred in history, typically in communities with precarious economic situations and enormous pressures, may tip the scales in the direction of mass hysteria. One of the most famous cases occurred in southern Italy, where the phenomenon was named “Tarantism” – after the tarantula spider that is responsible for causing the phenomenon. Residents of southern Italy believed that a spider bite caused an uncontrollable urge to dance.

16th-century medicine was still rooted in ancient theories, many of which dated back to the Middle Ages, particularly those attributed to figures such as Hippocrates and Galen. Doctors diagnosed the dancers as suffering from “hot blood,” a physiological imbalance they believed caused feverish behavior. Some doctors speculated that the extreme heat might have triggered the bizarre event.

Another term that may be relevant is chorea, or convulsion (from the Greek: “Chorea,” meaning “dance”) – a disorder of the nervous system, one of the manifestations of which is involuntary movements and spasms, which may resemble dancing. Despite the original name, there is no connection here with actual dancing or the dancing plague, nor with the bite of the tarantula spider, as was believed in the Middle Ages. The Italian peasant dance, Tarantella, is a fast dance, so named, according to one theory, due to the mistaken belief that a tarantula bite could cause the same convulsion, and, consequently, dance-like movements.

Cultural And Modern Effects Of The Dancing Plague

The Strasbourg dancing plague left a deep mark on European culture. The phenomenon has become a symbol of the power of mass hysteria and the dangers of superstition. Psychologists, historians, and anthropologists currently study it as a classic example of Social-psychological phenomena that are difficult to explain, even hundreds of years later.

In modern times, the event has resonated in popular culture, including musical and artistic works inspired by it. In 2020, English-Jewish director Jonathan Glazer created “Strasbourg 1518,” a short (approximately 10 minutes) musical horror film inspired by the dancing epidemic in Strasbourg. This short film features some of the world’s top dancers who perform in an unsettling manner, and it’s pretty creepy. Glazer, by the way, has been a very prominent name in the industry for decades, with 2023’s “Area of Interest“ earning him two Oscar nominations (Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay), and the science fiction-horror movie “Under the Skin”, featuring Scarlet Johansson. His impressive resume also includes video directing, such as Radiohead’s masterpieces “Karma Police“ and “Street Spirit (Fade Out)” and Jamiroquai’s iconic clip for Virtual Insanity.

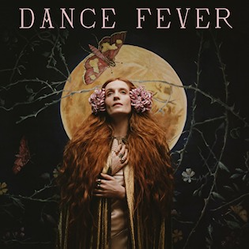

Speaking of music, there is no doubt that one of the most prominent influences of the 1518 dancing epidemic was on Florence Walsh’s British band “Florence and the Machine,” one of the writer’s favorite bands. In 2022, the band released their fifth studio album, called “Dance Fever”, an album whose concept is influenced by the social phenomenon of “Choreomania”, which is also the name of the third song on the album. The album overall explores themes such as dance, obsession, and loss of control.

For horror fans, we should note that one of the reasons that Florence and the Machine’s music in general and this album in particular is quite creepy, is related to the inspiration that Florence Walsh received from folk horror films such as “The Wicker Man” (1973. Well, if you ignore that bee’s find of the same name with Nicolas Cage from 2006), Francis Ford Coppola’s “Dracula“ from 1992 and prominent folk horror films from recent years, such as “The Witch“ (2015) and “Midsommar“ (2019).

More cultural texts relate to the dancing plague in one way or another, such as the graphic novel “The Dancing Plague” by Garth Brooks, the book The Dance Tree by British poet Kieran Millwood Hargrave, or the short film that promoted some of the songs by SAGES – the band of Eurovision winner and damned Swedish Lorraine and Icelandic musician Ólafur Arnalds.

What Can We Learn From The Strasbourg Dancing Plague?

The Strasbourg dancing epidemic remains one of the strangest and most terrifying phenomena in human history, or as you can call it: a serious trigger for those who abhor dancing. Whether the source was ergot infection, mass hysteria, or a combination of factors, the phenomenon reflects the complexity of the relationships between the mind and body, as well as between the individual and the community.

The fact that even today, almost 500 years after the event, we still do not know for sure what caused the plague or how many people actually died only adds to its mysterious and frightening atmosphere. The dispute over the number of victims highlights the challenges of determining historical truth, particularly in cases involving unusual phenomena.

Finally, the most important lesson for someone like me is that sometimes it is worth being grateful that my hatred of dance remains within normal limits, and that dance epidemics are no longer known today.

💀 Killer Deals & Scary Recommendations 💀

🎭 Costumes & Accessories

HalloweenCostumes Fun Costumes Entertainment Earth

🛒 Online Shopping

AliExpress Amazon Walmart Etsy

🧛 Collectibles & Horror Brands

Funko Hot Topic Lego Spirit Halloween

🎢 Attractions & Tours

GetYourGuide Tiqets Viator Klook

📖 Blogs & Horror Sites

Bloody Disgusting iHorror Fangoria

🩸 Disclaimer: Some links are affiliate links. The price stays the same – it just helps keep the site alive 👻